Resources nonprofit leaders can use

Since 1988, IFF has closed $1.4 billion in loans for more than 1,100 nonprofits, putting flexible capital in the hands of changemakers to help bring their visions for stronger communities to life. This year, we’re sharing some of what we’ve learned over the past 35 years to help nonprofit leaders better understand the types of loans available to nonprofits, how to leverage financing to amplify impact, how to evaluate and manage facilities projects, and more. If there’s a question that we haven’t addressed before that you’d like to know the answer to, we want to know! Email communications@iff.org, and we’ll do our best to cover the topic in a future piece.

When it comes to borrowing money, there are two numbers most people focus on: the interest rate – essentially how much a lender charges a borrower for financing – and the total monthly payments required to pay back the loan (comprised of principal and interest). What’s far less understood is how significant other factors can be in the total cost of borrowing money, like the term of the loan and the amortization schedule.

Before going any further, let’s define both concepts:

- The loan term is the period of time during which the borrower agrees to fully repay a loan.

- Amortization is how the repayment of the loan principal is spread out over a set period of time.

Understanding these factors is critical for any potential borrower to make good financial decisions, and especially for nonprofits – many of which operate with tight margins and/or limited liquidity. That’s because term and amortization impact not only the total cost of borrowing money, but the timing of cash outlays, including when payments for the loan will be due.

The pros and cons of longer amortization

A longer amortization period reduces the amount of cash the borrower is required to pay each month, but it also means the total amount of interest paid for the loan is greater over the term of the loan. With fully amortizing loans, the term matches the amortization, meaning the borrower will make payments each month during the loan term, and, at loan maturity, the balance of the loan will be zero and the loan will be fully repaid.

When the loan term is shorter than the amortization period, the borrower still makes monthly payments but there is a balance, called a balloon payment, due at maturity. This means the borrower must make a lump sum payment at the end of the term to satisfy their financial obligation to the lender or refinance the remaining balance and extend the period to repay the remaining loan obligation.

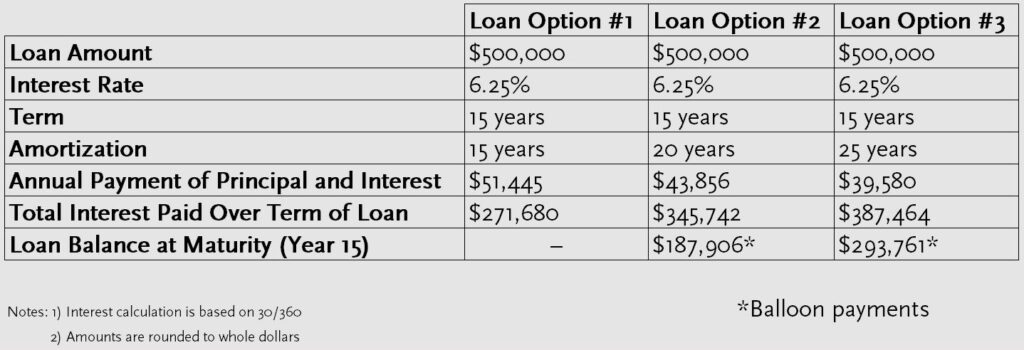

For an illustration of the impact of different amortization schedules, look at the chart below, which lays out three hypothetical loan options for a nonprofit facility project. While the amount of money being borrowed, interest rate, and term are the same for all three loan options, the different amortization schedules results in dramatic differences in annual cash payments, total interest paid over time, and loan balance at maturity.

It’s important to note that a shorter amortization isn’t inherently better than a longer one, or vice versa. The right choice for each nonprofit comes down to assessing the tradeoffs associated with a shorter or longer amortization schedule within the context of the organization’s specific needs, goals, and circumstances.

For nonprofits with operations that support a higher monthly payment, the loan with a 15-year amortization may look to be the best option because of the long-term cost savings associated with the loan, as well as the elimination of risk associated with a balloon payment (see the “refinance risk” bullet point below). And by paying off the loan more quickly, nonprofits also build “equity” in their investment more quickly resulting in increased net assets.

While Loan Option #1 may look attractive, it may not be the optimal scenario for all organizations given their operating model or other potential uses of funds. It may, in fact, be most beneficial to reduce monthly payments even if it does result in paying more in total over time.

In either case, there are a couple of additional items for nonprofit leaders to consider:

- Refinance risk: If the organization secures a loan with a term of 15 years and an amortization period of 20 years and is not able to pay the balloon payment (potentially a large sum!) at maturity, there is refinance risk. Approval of a new loan is not guaranteed, and terms may be less favorable. Additional costs are also likely (e.g., legal fees and origination fees)

- Prepayment penalties: A prepayment penalty restricts the ability of a borrower to repay the loan more quickly than the set amortization schedule. If there is no prepayment penalty, there may be more reason to choose a longer amortization since the organization has the flexibility to pay more than is required when it has the liquidity to do so to reduce or eliminate the balloon payment at the end of the term.

How to calculate the cost of any amortization schedule

Determining how different amortization schedules influence the total cost of borrowing money is pretty simple thanks to Excel. IFF has created a template worksheet that allows nonprofit leaders to enter any loan amount, interest rate, term, and amortization to determine how each variable influences the cost and cash requirements of borrowing money. For organizations ready to begin exploring loan options, the worksheet is a good first step in determining what options will work best.

To download the worksheet, click the image below.

For questions or additional information about amortization or other variables that influence the costs associated with borrowing, please contact IFF’s Capital Solutions team. Click here to read about how nonprofits across the Midwest have used IFF loans to amplify their impact.