The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was launched by the U.S. Small Business Administration to help small businesses, including nonprofits, keep employees on payroll, even as pandemic safety measures forced them to close or reduce services. The program ran from April 3 – August 8, distributing more than 5.2 million loans worth more than $525 billion.

When the program first launched in the spring – when small businesses and nonprofits were panicking over revenues that plunged overnight – many of the smallest of the small businesses reported that they were struggling to access this critical program. This was even more true for small businesses led by people of color.

Online portals were crashing. Phone lines were jammed. Headlines were reporting that big, connected businesses were getting a disproportionate share of the funds. And the (first round of) funds were running out.

Nonprofit leaders were losing hope.

This is the CDFI way – We see a problem, we try to fix it. We see a gap, we try to fill it. We can’t do something alone, we find a partner to go further together.” –Joe Neri, IFF

IFF went into problem-solving mode.

“We considered becoming an SBA lender ourselves, but we knew that might take time – precious time for nonprofits experiencing real-time struggles,” says Matthew Roth, IFF’s President of Core Business Solutions. “We decided the best, most expedient, and most effective way forward was to form a partnership with a fellow CDFI that had a long history of SBA lending: Community Reinvestment Fund, USA (CRF).”

CRF provided crucial training to IFF’s staff to prepare them for SBA guidelines, procedures, and systems. Additionally, CRF allowed us to access their proprietary SBA platform that was integrated with SBA systems and allowed us to see the progress of each loan application in real time.

In return, IFF committed a huge number of resources to reach nonprofits, deploying all 11 of our loan officers as well as three financial analysts, our entire lending management team, all of our administrative support, and staff from our communications and research teams. By the time the SBA announced the second round of funding, IFF staff was ready to process hundreds of inquiries and loans.

“The partnership was a perfect match: IFF knew nonprofits, and CRF knew SBA programs,” Roth says. “CRF’s training and system made for a very smooth process, which enabled IFF to respond to clients within 24 hours – something very much welcome by the nonprofits who had already spent weeks waiting for their bank to return their call.”

That sentiment was shared in interviews and emails with dozens of our PPP clients. One leader from Cincinnati put it this way:

“When PPP first came out, the biggest reason we started having anxieties was our bank. I messaged them once a week saying: ‘Where are you? What do I need to do? Please give us some information. We need to apply. We’re desperate.’ No response, no response, no response. When the first round of money ran out, we really started to panic,” says Daniel Traicoff, Executive Director of Mt. Airy CURE, a nonprofit community development corporation. “I reached out to IFF and got a response back in less than 24 hours. Almost instantaneously, we got a meeting scheduled, they told me what to do, and we got it done.”

Together, IFF/CRF closed loans totaling more than $21 million for 159 nonprofits throughout the Midwest.

And while loans were still being processed, we formalized another collaboration with a long-time partner, Fiscal Management Associates (FMA), to help ensure nonprofit PPP borrowers have the tools they need to receive loan forgiveness.

These partnerships kicked off a flurry of outreach, an influx of new clients, countless stories from nonprofits working on the ground to help their communities, and a mixture of data that shows that some help was provided, conclusions are hard to draw, and much more needs to be done.

Reaching out to the left out

IFF tried to interrupt the unjust patterns we saw by offering equal PPP access to all nonprofits – regardless of their size or borrower status.

IFF tried to interrupt the unjust patterns we saw by offering equal PPP access to all nonprofits – regardless of their size or borrower status.

“Borrower status is often tied to size, and size is often tied to race, so this is all interconnected,” says IFF CEO Joe Neri. “Even IFF’s typical customer base, which focuses on nonprofits ready to purchase real estate, leaves out some of the smallest and newest organizations. That’s why IFF intentionally reached beyond our existing customer lists through philanthropic partners and a whole lot of proverbial shoe leather.”

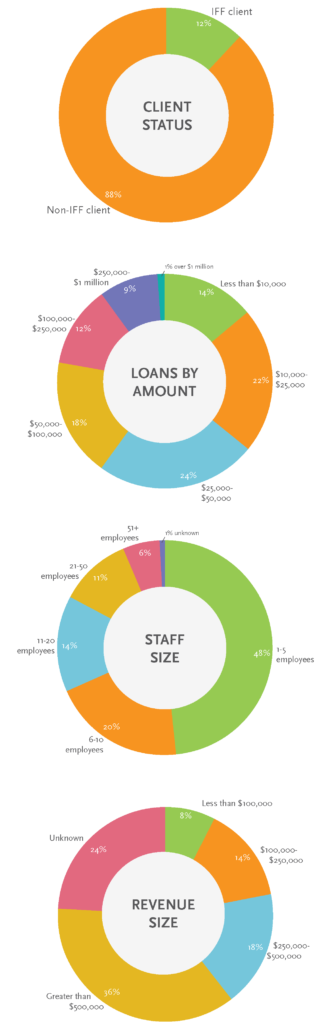

Only 19 of the 159 PPP borrowers that went through IFF were previous IFF customers – a clear victory on the borrower status front. But were those nonprofits smaller than those being reached by the SBA more broadly?

“As a data-driven organization, we tried to look for metrics to assess our success in reaching smaller nonprofits. But the way the SBA released their data makes that tricky,” says Tara Townsend, IFF Vice President for Research and Evaluation. “For one thing, the data released about larger loans is different from the data released about smaller loans. That makes it impossible to make an apples-to-apples comparison between all PPP loans and nonprofit PPP loans, or between all nonprofit PPP loans and IFF’s nonprofit PPP loans.”

But the metrics we do have on loan size, revenue size, and staff size indicate some success on IFF’s goal to reach smaller nonprofits:

- Loan size: At IFF, no loan size was too small. Our smallest PPP loan was just $900, and our median loan size was $40,000.

- Revenue size: The median annual revenue of IFF’s PPP borrowers was $479,000. “That amount is even smaller than our average nonprofit borrower, and we serve nonprofits that aren’t typically served by traditional financial institutions,” Roth says.

- Staff size: The average number of employees at IFF’s PPP borrowers was just 16 – and more than half of our loans went to nonprofits with only 1-5 employees on staff.

Whether IFF specifically reached nonprofits led by people of color was even harder to assess with the data because race and ethnicity is a self-reported and optional field on the SBA application. Only 9% of nonprofits receiving PPP funding completed the question, and, of those, only 1% were organizations led by people of color. Of IFF’s 159 nonprofit PPP borrowers, only six completed the question and four were led by people of color.

“Missing data on race has been a persistent problem for the nonprofit sector, and beyond,” Neri says. “We can’t know for sure how many leaders of color we reached. But we do know that smaller organizations often fly under the radar of larger financial institutions, and our 33 years of experience working with nonprofits tells us that the proportion of smaller nonprofits led by people of color is higher.”

IFF wasn’t the only CDFI fighting for equal access to the PPP. In fact, CDFIs and MDIs – Minority Depository Institutions – successfully organized to advocate for a set-aside of PPP funding for smaller financial institutions in the second round of funding. And data shows that CDFIs and MDIs made up only 10% of PPP lenders but made 14.5% of PPP loans – which represented nearly 16% of dollars lent.

“This is the CDFI way – We see a problem, we try to fix it. We see a gap, we try to fill it. We can’t do something alone, we find a partner to go further together,” Neri says. “And, at the heart of it all, has always been a focus on equity, on getting dollars into the hands of the people who most need it because they have the least access to it.”

Lessons in forgiveness

Getting the loan was only half the battle. Once secured, nonprofits had to turn to the task of making sure their loans will be fully ‘forgiven’ – essentially, turned into grants if a specific set of criteria is followed closely and reported accurately.

With nonprofits scrambling to keep up, IFF turned to FMA – which has decades of experience advising nonprofits on how to navigate tough financial waters – to make sure our participants had access to information and guidance on how to maximize their chances at full forgiveness.

“There’s a long history – perhaps well-intentioned, but also systemically clueless – of governments offering assistance and then…there’s a catch.” -Tara Townsend, IFF

Since the COVID-19 crisis began, FMA has provided nearly 160 live clinics attended by more than 5,000 individuals as well as published on-demand webinars viewed by more than 1,200 others. The organization’s online PPP Toolbox has been viewed by 65,000 individuals.

Six of those clinics and webinars were sponsored by IFF through a grant provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

According to IFF research head Townsend, access to information on the PPP loan forgiveness process is another issue of equity.

“There’s a long history – perhaps well-intentioned, but also systemically clueless – of governments offering assistance and then…there’s a catch,” she says. “That’s why it’s enormously critical that nonprofits – especially those without access to expensive consultants, lawyers, and accountants – have all the information they need to make sure these loans get forgiven and don’t become another burden. Without loan forgiveness, the PPP would end up exacerbating the very problem it intended to alleviate.”

The human connection

In a survey conducted by FMA, nonprofit PPP borrowers shared that their most commonly reported challenges in navigating the application process were: inconsistent guidance on the program, communications challenges with their bank, funding running out before their application could be processed, and glitchy online portals.

In Their Own Words

As IFF lenders and our partners at CRF communicated regularly with our PPP borrowers, we received many unsolicited words of thanks. With their permission, we are publishing some of them here to illustrate the human side of a financial transaction. Some quotes are also taken from the collection of PPP borrower stories we published.

See quotes.

“Many nonprofits said they had been banging their head against the wall trying to get basic information, and then they came to IFF, and we sometimes got the loan documents processed in less than 24 hours,” Lieberman says. “But the thing we heard the most was just how nice it was to talk with a human being and to not be left in a ‘black hole’ of communications.”

As Pastor Leon Stevenson of Detroit’s MACC Development put it: “Getting approved was great. But even if we had been rejected, even if we hadn’t gotten the money, the help IFF provided during a time when the small organizations felt like no one else was giving guidance — that was a great blessing to us. We felt like we had people in our corner.”

That kind of support is what IFF is all about.

“As a financial intermediary, we’re often doing things one might describe as ‘procedural’ or ‘advisory,’ which doesn’t sound very warm and fuzzy. But the nonprofits we worked with on the PPP felt heard by us – they called us, they cried with us, they thanked us. This human-centered approach is part of our secret sauce – and it underscores IFF’s Continuum theory,” Neri says. “You can’t just make a pot of money available and walk away; nonprofits and communities need a continuum of support to equitably and responsibly access and leverage those funds. A big part of the reason why the CDFI Fund and our financial institution partners continue to invest in us is because they know this works.”

Tags: : Arts and Culture, Capital Solutions, Early Childhood Education, Health Care, Healthy Foods, Housing, Schools, Universal Access